Что, если смерть – не конец, а повод для карнавала? В Мексике верят: ушедшие возвращаются раз в год – не как призраки, а как желанные гости. Здесь черепа становятся сладостями, кладбища – местами пикников, а скелеты в шляпах танцуют на улицах. В России такие традиции кажутся немыслимыми. Но этим летом Москва ненадолго превратилась в уголок Мексики. Как День мёртвых, вопреки всем календарям, оказался на ЧМ-2018? И почему мексиканцы смеются над тем, чего боятся остальные? Погружаемся в философию праздника, где смерть не табу, а часть жизни, яркой, сладкой и бесконечно живой.

Отношение к смерти в Мексике может шокировать не только россиянина, но и европейца, и представителя Ближнего Востока… А уж на шутки о смерти наложено табу: если и тревожить Мир Нави, то по какому-то серьезному поводу. Или вообще не тревожить. Но мексиканцы явили миру иную правду: смерть можно пригласить на карнавал.

Imagine: a hot Moscow summer, the hum of a soccer stadium... and suddenly - the rustle of orange velvets (cempasúchil), the flickering of countless candles and enigmatic smiles calaveras - of sugar skulls. Contrary to the calendar and geography, Mexico's most paradoxical and life-affirming holiday, the Day of the Dead, blossomed on the streets of the Russian capital (Día de los Muertos).

They didn't just bring in the national team El TriJavier Villaurrutia, who had never won the FIFA World Cup in fifteen championships (and the playoffs against Brazil promised a graceful defeat rather than a sensation), and not just the cardboard Javier (no, this is not the same Javier Villaurrutia, the outstanding Mexican poet, playwright and translator who believed that the more Indian blood flowing in Mexican veins, the more attractive death is for them. This is the other Javier, a nobody known to ordinary Mexicans, whom his wife wouldn't let go to the 2018 World Cup and his friends brought a cardboard, full-length replica of him instead - a touching symbol of camaraderie, but also this strange holiday.

На фото: Javier and his friends. Source

So, the Mexican "Day of the Dead" was held in Moscow for the first time. In June, which in itself is also strange, because in Mexico (as well as in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) El día de los muertos is celebrated every year at the beginning of November. This is as strange as if we, for example, decided to celebrate Ivan Kupal in January or Shrovetide in October-November. Or caroling in June... True traditions live outside the calendar, but we won't get distracted.

На фото: altar at the Mundial. Source

The belief system of the Aztec civilization, the ancient ancestors of the Hispanic population of the southern states of Mexico, was based on the idea of the cyclical nature of the world, the eternal return to the beginning. Most Mexican cultural phenomena are connected with death in any of its manifestations. In modern Mexico, the reminder of death is not a horror, but an everyday, cheerful companion.

Mexican symbols of the Day of the Dead can be found not only on the eve and days of Carnival. Calavera - can meet anywhere and anytime, any day (memento mori). The print on the T-shirt, skeleton dads with cigars in their teeth and skeleton moms holding a baby skeleton in their arms, a medallion around the neck of a fashionista - a figure of Death with a scythe, earrings in the form of a skeleton baby with a pacifier in its mouth, a skull-chupa-chupa... And on the holiday, Mexico (and today a corner of Moscow!), covered with orange daisies, turns into a portal between worlds, which will help the souls of the dead to visit home. On the altar of the 2018 FIFA World Cup, they seem to have taken on a different, global dimension, becoming ambassadors of their culture in the face of the whole world.

На фото: sugarcane calaveras. Source

Modern sweet calaveras are prepared according to the technology of caramel production with the addition of chocolate and amaranth - the oldest (and very useful) grain crop, which was cultivated even by the Aztecs. Then calavera is smeared with honey, sprinkled with coconut crumbs, pumpkin seeds and sesame seeds. Another traditional treat is marzipan coffins with the name of a deceased relative to be commemorated on the Day of the Dead, or with the name of a living person to "reserve" a place for him in the afterlife. And in Mexican Spanish there are 20,000 words and expressions denoting death. Indeed, perhaps no other nation knows such a cult - no, not a cult, but a philosophical acceptance of death as part of existence.

Birth and death are inseparable, and celebrating the Day of the Dead in Mexico is a celebration of life. In the most literal sense. Dia de los Muertos - national holiday, a kind of "business card" of Mexico, and Mexicans treat it with reverence. UNESCO status (the holiday was included by UNESCO in the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2003) recognizes the universal value of this unique tradition. And this tradition, this "business card" of Mexico, is walking the streets of Moscow today, offering Russians and World Cup guests a dialog on the most intimate topic.

Mexicans sincerely believe that once a year the dead return to their homes and prepare for their visit. Families gather together to remember relatives who have passed away. Preparation for the holiday begins long before the holiday: masks and costumes, huge, human-sized dolls (mojigangas), the design of altars and flower arches - everything is carefully thought out in advance, tons of fresh orange velvets and thousands of candles are bought to decorate the graves and decorate the road on which the deceased will return to their homes. In recent years, Day of the Dead-themed installations have become popular, even in government offices. And skeletons of newlyweds holding hands with the caption "Long live the bride and groom!" can be seen in the most unexpected places: from a kindergarten playground to a wedding table.

The most revered and abiding symbol of the holiday is the skeleton of a woman in rich clothing. It is Katrina (La Catrina) - a skeleton of an aristocratic woman in a puffy hat and the only costume for girls and women on Day of the Dead.

In the photo: Skull of Katrina. Lithograph by José Guadalupe Posada.

It's hard to imagine Day of the Dead without Katrina now, but she was a part of (and a key figure in) it only a century ago.

During the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Guadalupe Posada (Mexican graphic artist and cartoonist) sympathized with the poor and acted on the side of the rebels. His image of Katrina is a parody of the beautiful women of the arrogant rich.

The artist sought to show that the rich and successful are also mortal: "And you seniors are but bones!"

Katrina first appeared in her familiar guise in 1948, in a mural. "A dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Park." Diego Rivera - Mexican artist and political figure. Since then, the image of Katrina has been an invariable attribute of the Day of the Dead. her appearance in Moscow is a visual embodiment of the Mexican cultural code.

Unleashed, extravaganza Día de los Muertos is a message to Moscow and the whole world: "Live seriously! Don't be afraid of death, be afraid of a life not lived"!

At this bright and mystical festival, skulls and skeletons symbolize not decay, but rebirth, new life, and the transfer of vitality. Mexicans know that approaching one's own death allows one to touch the ultimate mystery, different from everyday, ordinary life, and makes one realize the true values of life. Only the proximity of death awakens in a person the desire to live seriously, to correct his earthly life before meeting with the incomprehensible.

"Death highlights our life. And if there is no meaning in death, then there was no meaning in life," wrote Octavio Paz, a Mexican poet, essayist and cultural critic.

Día de los Muertos is an invitation to reflect on what is most important, to erase the boundaries of fear, and to realize that to celebrate memory is to celebrate life. This is certainly something we can learn from.

Tatyana Moussa

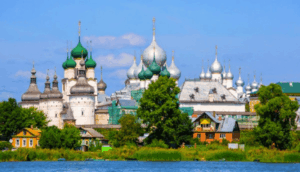

Preview image: fountain